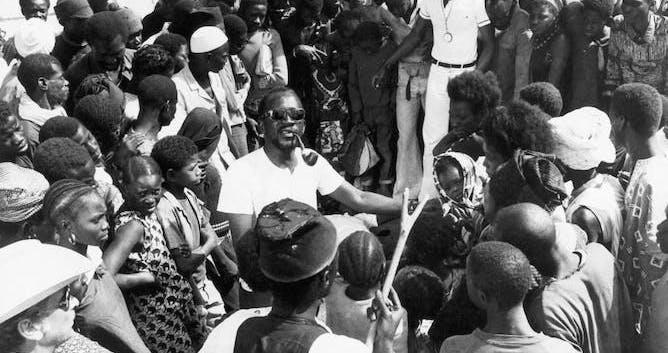

Born 100 years ago this year, Africa's most legendary filmmaker – and a prolific novelist – remains relevant through his beautifully crafted political works.

January 1, 2023 marks the centenary of the birth ofOusmane Sembene, the Senegalese novelist and filmmaker hailed as the “father of African cinema”. Over five decades, Sembène has published 10 books and made 12 films across three distinct periods. He was popular for his beautifully crafted political works, ranging in style from psychological realism to The Black of…) in 1966 to the biting satire of shawl (The Curse) in 1974.

Since his death in 2007, Sembène's status as a pioneer has continued to grow. But the variety and richness of his work, his ability to reinvent himself as an artist, have often been overlooked. On the occasion of his centenary, it is worth reflecting on what made him such a remarkable creative presence.

The novelist: 1956-1960

Unlike many of his literary peers, Sembène did not come to writing through the colonial education system. In fact, he left school very early and became self-taught. He was born into the Lebou minority community in the Casamance region of southern Senegal. His father was a fisherman. He then moved to Dakar, the colonial capital.

After having served in the French army during the Second World War, he moved to France in 1946. Employed as a docker in Marseilles in the 1950s, he developed a passion for literature by frequenting the library of the syndicate of obedience communist, the General Confederation of Labor. Her first novel, The Black Docker (1956), consciously explores the difficulties faced by a working-class black writer who seeks to become a published author.

Sembène's most famous novel, Les God's Pieces of Wood (1960), is a fictionalized account of the 1947-1948 railway strike in colonial French West Africa. This vast epic, which takes place in three different places and features a multitude of characters, illustrates the vision Marxist et panafricanist of Sembene's anti-colonialism. He believed that the overthrow of colonial powers could best be achieved through working-class alliances across national and ethnic lines.

God's Bits of Wood is often described as Sembène's classic text, politically engaged and realistic in his style. However, it turned out to be the culmination of his exploration of literary realism.

In 1960, he returned to Africa after more than a decade spent in Europe to visit a continent liberated from colonial rule. He is famous for saying that, sitting on the banks of the Congo River, watching the teeming masses, most of whom could not read or write, he had an epiphany. If his novels were inaccessible to many Africans, cinema was the solution. He sets out to become a filmmaker.

Novelist and filmmaker: 1962-1976

After studying cinema in Moscow, Sembène directed his first short film, Borom Sarret (Le Charretier), in 1962. This film, which recounts the day of a modest carter, is a sharp criticism of the failures of Senegal's independence, presented as the transfer of power from one elite to another. Like most French-speaking African countries, Senegal gained its independence in 1960. It would be governed for the next two decades by the Socialist Party, led by the poet Leopold Sedar Senghor, which seeks to maintain close political and cultural ties with France.

Between 1962 and 1976, Sembène published four books and made eight films, works of incredible aesthetic diversity. This is perhaps the richest period of artistic productivity of any African writers and directors of the postcolonial era. Sembène has achieved a series of firsts for a black African director: first film made in Africa (Borom Sarret), first feature film (La Noire de …), first film in an African language (mandabi).

He began to gain international fame, but opportunities to see his work at home were rare. Mandabi (Le Mandat), for example, won an award at the Venice Film Festival but was not released in Senegal, where it was criticized by the government for presenting a negative view of the country.

Between 1971 and 1976, Sembène made his most ambitious trilogy of films: Emitai, Xala and ceded. These films are driven by strong plots. But most important to Sembene is a film's ability to condense social, political and historical realities into a series of gripping images. These often blur the boundaries of space and time.

In Ceddo, he condensed several centuries of history into the life of a Senegalese village, resulting in a struggle for power between theanimism, Christianity and l'Islam. The latter imposed himself by force of arms, a controversial position in a country which was then more than 90% Muslim. Ceddo was banned by Senghor, Sembène's sworn enemy. He will not make another film for more than ten years.

Wild Years to Late Blossom: 1976-2004

After a decade spent in the creative desert, Sembène experienced a late blooming from the end of the 1980s. It then touched a new generation of spectators. His later works are less aesthetically ambitious, but just as powerful.

his masterpiece, Moolaade (2004), is a scathing denunciation of female genital mutilation in rural West Africa. In this work, the forces of change oppose patriarchal and conservative authority. The images of radios of the women being burned by the men in front of the village mosque are a stark visual depiction of this conflict. As in his earlier films, what matters are fundamental power relations, not a closely observed realism that depicts the world as it is but cannot imagine how to change it.

Sembene today

Since Sembène's death, we have learned more about his life and career through the painstaking work of his biographer. Samba Gadjigo, who is also co-producer of the documentary Sembene! (2015). Sometimes what the Senegalese writer and scholar has learned has been negative – including Sembène's 'stealing' of the film idea Thiaroye Camp (1988) to two young Senegalese creators. But it's a necessary part of overcoming the over-reverent accounts that sometimes pass for discussions of Sembène's career.

The recent opening of Sembene archives at Indiana University offers scholars a new opportunity to deepen their understanding of his life and work.

Those unfamiliar with Sembene should pick up a copy of his novel Les Bouts de bois de Dieu or find recent DVD editions of classic films such as La Noire de... or Xala (of which the opening sequence is part, in my opinion , of the five best minutes of all African cinema).

My favorite film is his tragicomedy Mandabi, recently reissued in a restored version. Under the guise of a simple story of a poor man trying to cash a money order, Sembène weaves a brilliant critique of capitalism and the power of money to undermine social and family ties.

In Paris, the Cinémathèque française marks the centenary of Sembène's birth with a retrospective of his films.

Sembène's films are still relevant, not only because of the relevance of many of the social and political issues they address. But also because he knew how to create a cinematographic language which knew how to touch the public of the whole world.

He forged a career that spanned five decades, while many of his contemporaries struggled to make more than a handful of films. This creativity and longevity have helped shape African cinema in complex ways: contemporary directors may follow in Sembène's footsteps or choose to reject his politically engaged style, but his legacy cannot be ignored.

David Murphy, Professor of French and Postcolonial Studies, University of Strathclyde

This article is republished from The Conversation under Creative Commons license. Read theoriginal article.