The argument of epigenetic damage caused to the descendants of slaves has recently been invoked to seek compensation from the French State for the crimes of the slave trade. Decryption.

Have you heard of epigenetics? This term, coined eight decades ago to account for the essential role of genes in theembryogenesis (the early stages of embryonic development) and more generally in the development of living organisms, has since taken on many other meanings.

It is most often invoked today to mean that genetic variations do not explain all of the differences between individuals and that the environment, taken in the broad sense, largely shapes who we are. How ? By durably modulating the functioning of genes, without however changing the DNA sequence.

In the way the sociologist Alondra Nelson did it for genetics, current events invite us to study the public circulation of the term "epigenetics" as well as the diversity of its uses outside the scientific community.

Fix slavery

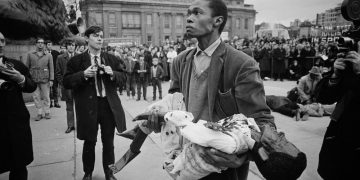

Thus, on January 18, the Fort-de-France court rendered a much-awaited judgment in the context of a request for reparation and compensation for the crimes of the slave trade and slavery by the French State.

This judgment is part of a judiciary process initiated in May 2005 by two associations, the International Movement for Reparations (MIR) and the World Council of the Pan-African Diaspora (CMDPA).

It comes to close a more recent sequence, opened on the occasion of the historic trial which was held in Fort-de-France on October 11 and 12, 2021.

During this trial, the lawyers of the MIR put forward a new argument for the civil parties, that of epigenetics.

“There is epigenetics, it is the last revolution”, had thus indicated to the judges Maître Evita Chevry, defense of the MIR. According to the latter, this new science would “explain the genetic transmission to the descendants of slaves of trauma and stress-related reactions”.

On January 18, 2022, the Fort-de-France Court of Appeal declared the claim for compensation inadmissible. But Garcin Malsa, former separatist mayor of Sainte-Anne and president of the MIR declared to appeal in cassation by invoking, again, research in epigenetics:

“We are going to demonstrate to them that from a scientific point of view, based on epigenetic reports, that in our population, in black populations, well there is a degree of causality between slavery and hypertension by example, diabetes…”

If the legal recourse to an epigenetic argument is still rare, it has already appeared in the West Indies in the so-called chlordecone affair, a pesticide widely used in banana plantations in Martinique and Guadeloupe. We find it like this in a complaint, sometimes brought by the same lawyers as for the request for compensation.

The biological imprint of trauma

In the case of slavery and the slave trade, the complaint is based on work exploiting recent advances in DNA sequencing to identify the biological imprint left by situations of extreme adversity (war, genocide, famine, etc.), their effects on health and their possible transmission through the generations.

Among these reference works, those of the team led by Rachel Yehuda on the descendants of Holocaust survivors or other people facing a situation of extreme adversity obtained a significant media coverage.

We can also cite those of Grazyna Jasienska who, as early as 2009, relied on advances in epigenetics to defend the idea that successive generations since the abolition of slavery in the United States (1865 ) were not enough to erase the impact of slavery on the contemporary biological and health status of the African American population.

The emergence of this work in the West Indies is to be linked with the symposium "Slavery: what impact on the psychology of populations" organized in 2016 by Aimé Charles Nicolas, professor of psychiatry and addictology.

On this occasion, Ariane Giacobino, doctor and geneticist, presents the state of research, sometimes exploratory, in epigenetics.

The administration of the proof remains to be done

Are the lawyers of the MIR right to see in epigenetics a scientific support to defend their cause? In other words, does scientific research in the field of epigenetics prove that it is possible to inherit the trauma of slavery?

A study of the state of knowledge indicates that, as with many other emerging research fronts, most of the administration of proof remains to be done.

Indeed, if the possibility of intergenerational transmission (from parents to children or even to grandchildren) of physiological or behavioral alterations induced by pollutants or extreme situations is beginning to be well documented – see the works of Edith Heard and Robert A. Martienssen ; those from Sanne D. van Otterdijk and Karin B. Michels or even those of Conin C and Oliver J Rando -, it is nevertheless most often limited due to molecular mechanisms of epigenetic reprogramming between generations, mechanisms essential to reproduction and normal development of the embryo.

Moreover, a transmission beyond a few generations remains difficult to conceive because of the genetic differences within the couple which gives birth to a child. These differences “reshuffle the cards” with each generation and influence to varying degrees the epigenetic state of carrier individuals.

And finally, more fundamentally still, human societies are characterized by a considerable degree of socio-cultural heritage, the effects of which are visible everywhere and at every moment. In this context, proposing that an epigenetic transmission, moreover over a long period of time, of the damage and suffering suffered by populations is the primary cause of the difficulties their distant descendants face raises questions.

Should we conclude that the lawyers of the MIR are on the wrong track and that this detour through biology can only weaken a legitimate cause?

If the decision of the court of Fort-de-France shows the legal ineffectiveness of the use of epigenetics, its social and political effects should not be underestimated and this for at least three reasons.

A publicized and internationalized subject

Firstly because the lawyers of the MIR address themselves as much to the judges of the court of Fort-de-France as to the Caribbean civil society as a whole. Beyond justice, it is civil society that they wish to convince.

The study of the public circulation of epigenetics shows that the general public is fascinated by the idea of a hereditary transmission of trauma. Moreover, the media coverage obtained by often spectacular exploratory work make scientific debates on these issues difficult to hear Result: this notion of epigenetic transmission of trauma can constitute a vector of social and political mobilization even though it is not, at this stage, scientifically confirmed.

Then, through this reference to epigenetic heredity, the plaintiffs reopen an already well-fed public debate on the nature of the heritage of the former French colonies in America.

These territories experience repeated social crises, in particular because they concentrate social inequalities greater than those observable in mainland France. These inequalities have a tragic historical source with slavery. Epigenetics can then appear as an additional resource for accounting, here and now, for the extent of these inequalities, particularly in terms of health.

Finally, by explicitly referring to epigenetics, the lawyers of the MIR take their place on the world map of movements for the request for historical reparation which, as in the West Indies, mobilize advances in epigenetics.

Indeed, where the reference to genetics has frequently been rejected by activists or associative militants refusing to biologize the cause of the descendants of oppressed populations, epigenetics through the interdependence of biology and the social and cultural environment it assumes, seems more acceptable, including in the process of biological transmission of lived experiences that it would allow.

Epigenetics is constructed in terms of a “political biology” present in claim contexts similar or very different to the Canada with the issue of "boarding schools" imposed on Aboriginal children, in Australia with the colonial violence inflicted on the aboriginal populations, the USA with the consequences of slavery or in South Africa with a post-apartheid society that remains deeply marked by racism.

This global circulation of the term "epigenetics" in the name of the values of emancipation and social justice does more than illustrate the diversity of social and political uses of science. It shows how its advances, even the most exploratory ones, fuel new forms of collective mobilization on an international scale.

Michael Dubois, CNRS Research Director, Sorbonne University; Catherine Guaspare, Design Engineer, National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS)and Vincent Colot, Director of recherche, École normale supérieure (ENS) - PSL

This article is republished from The Conversation under Creative Commons license. Read theoriginal article.

![[Editorial] 30 years later, is apartheid really over?](https://lejournaldelafrique.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/caricature-jda-apartheid-360x180.jpg)

![[Edito] Gabon and Commonwealth: the whims of Prince Ali](https://lejournaldelafrique.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/caricature-JDA-Bongo-360x180.jpg)

![[Editorial] Facebook and Twitter, more dictators than dictators?](https://lejournaldelafrique.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Caricature-JDA-FB-TW-360x180.jpg)

![[Edito] Rwanda: for the French apologies, we will have to go back](https://lejournaldelafrique.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Caricature-rwanda-JDA-360x180.jpg)

![[Edito] Guinea: Alpha Condé, the oppressed turned oppressor](https://lejournaldelafrique.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Caricature-Alpha-Conde-360x180.jpg)

![[Edito] CFA Franc: a facelift cut to measure for France](https://lejournaldelafrique.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Caricature-JDA-CFA-360x180.jpg)

![[Edito] Riyad Mahrez: One, two, three, viva l'Algérie!](https://lejournaldelafrique.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/caricature-Mahrez-360x180.jpg)

![[Edito] Niger: Mohamed Bazoum begins a delicate balancing act](https://lejournaldelafrique.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/image_6483441-1-360x180.jpg)