Burundi, although it is no longer at war, is nevertheless faced with serious political and economic difficulties, writes Professor André Guichaoua.

Burundi, which celebrates this 1er July the 60th anniversary of its independence, is the poorest country on the planet in terms of GDP per capita. This sad observation must be understood in the light of a history punctuated by many dramatic events. Until 1996, the country lived to the rhythm of coups, massacres, political assassinations… before plunging into a long civil war. Peace was gradually restored in 2003. However, it returned to authoritarian governance in 2015.

Since then, the UN has noted progress but continues to denounce the political violence that plagues the country. How did Burundi come to this and why is its lot not improving?

Establishing authorities capable of establishing peace: the 2005 elections

In 2005, after 25 years of pro-Tutsi military regimes (at that date, the country's two main ethnic groups: Hutus and Tutsis, accounted for 85% and 14% of the population respectively) and ten years of civil war, the voters wanted peace and brought to the presidency Pierre Nkurunziza, the head of the National Council for the Defense of Democracy – Forces for the Defense of Democracy (CNDD-FDD), the most powerful movement of the Hutu rebellion, capable of imposing itself both vis-à-vis the army regular forces, the Burundian Armed Forces (FAB), than ex-rebellions from the Hutu camp.

The position of strength of the CNDD-FDD (dissident armed branch of the CNDD, which had agreed to sign a ceasefire with the power in place in 1998) was not assured. Its primacy had to be validated electorally while the process of negotiation between political parties andelaboration of the constitutional framework had been conducted without his participation.

Five years of political settling followed during which the CNDD-FDD completed its national establishment.

Consolidating the restored peace and the stability of the political framework: the 2010 elections

Faced with a divided opposition, the local CNDD-FDD candidates and the charismatic personality of the incumbent president enjoy massive support from rural populations. The aspiration for stability is all the stronger since, for the first time in the country's history, voters are called upon to vote at the normal end of an election.

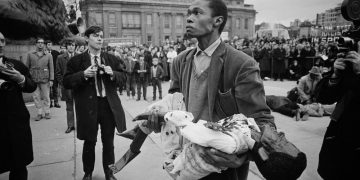

Provided by the author

But beyond the realism, the strong electoral participation and the scores obtained by the CNDD-FDD express a real satisfaction towards a party which knew how to appease the ethnic divisions and succeeded in the integration of the armed forces, now under the control of the executive. This national "reconciliation", particularly vis-à-vis an army that no longer "fears the population", was the determining factor in the victory of the CNDD-FDD.

With full powers at the various levels of national representation, its leadership immediately got involved in the electoral campaign for 2015. The absolute priority given to the management of local problems, to strengthening the supervision of the populations, the structuring and mobilization of the party's militants and executives are commensurate with the objective: to retain all power in the long term.

The coup de force of Pierre Nkurunziza's "third term": the 2015 elections

Having succeeded, in ten years of exercise, in concentrating in his hands the tools and resources of power and establishing a single party de facto endowed with a youth militia responsible for the local supervision of the populations and the neutralization of any organized opposition, it then seemed unbearable to the president to have to give up his prerogatives.

On April 25, 2015, after the party's confirmation of the outgoing president's candidacy, popular protest was immediate and strengthened despite police mobilization. the Failed military coup of May 13, followed by violent repression, exposes the fractures within the armed forces. The generation of freedom of expression and independent media, which aspires to democracy without having really experienced it, is submissive.

In July, after elections neither free nor credible according to the UN, the CNDD-FDD exceeds the two-thirds majority in the National Assembly, which is the percentage necessary to emancipate itself from constitutional constraints and Arusha Accords to reappoint the president as head of state.

The 2020 electoral bailout

In addition to the repression of opponents, economic tensions are worsening: sluggish growth, capital flight, lack of infrastructure maintenance, looting of public resources and a sharp reduction in social benefits are deterring international aid.

At the end of his third term, the leaders of the CNDD-FDD are pushing the "eternal supreme guide" who has become "unpresentable" towards the exit. They elected in May 2020, following a contested election, General Évariste Ndayishimiye, a informed and withdrawn man of synthesis. Nkurunziza dies shortly after from Covid-19, a disease whose danger he had always underestimated.

While the party-state controls all powers and resources, regulates the daily lives of citizens and no longer has an internal "enemy" beyond its control, the assessment of the three mandates CNDD-FDD governance is catastrophic. Managerial impotence and economic escheat have reached unprecedented levels on a regional and international scale.

Economic bankruptcy, structural constraints and democratic aspirations

This is not a temporary epiphenomenon since the GDP, already very low at the beginning of the 1990s, continued to fall after 1993-1994 and then the civil war. At its lowest in 2005, it rose again from 2005 to 2014, then has continued to fall since the 2015 crisis. and has remained there ever since. At the same time, the public debt is progressing and the public account deficit is widening. However, a timid recovery in growth will prevail in 2021.

The Human Development Index of the United Nations Development Program (UNDP), which includes the criteria of longevity, education and inequality, also attests to the impressive deterioration of the country: 138e world rank out of 189 countries in 1995, 169e in 2000, 182e in 2005, 180e in 2010 and 2015, 185e and in 2019 2020.

Provided by the author

Thus, in almost all economic and social areas, Burundian performances are among the lowest on the planet, without any constraint new cannot be invoked. On the contrary, taking precedence since 2012 over traditional coffee and tea exports, gold and more recently rare earths (2019 - 2022) are among the first export posts of the country.

Potentially promising, but fatal for farmers on devastated lands, it is however difficult, if not impossible, to accurately assess the dividends derived from the mining sector, due to the overall lack of transparency and the complexity of the arrangements between the multiple national and international partners.

The "people of the hills" facing their elites

After the April 2015 coup, the co-management of the “integrated armed forces” (ex-FAB and rebellions) and the balance that prevailed between the army and the police came to an end. emerged victorious from the putsch, the recent officers from the rebellion no longer imposed any limits on themselves in terms of financial catch-up and “career delays” vis-à-vis their older Tutsi colleagues and graduates of military schools. Hitherto contained or concealed (ICG, 2017), these practices were transformed into an open competition for personal enrichment commensurate with each person's powers.

If we add the security tensions of the local supervision of citizens by the CNDD-FDD party, one might think that the "new inclusive democracy" of the military elites from the maquis has not fundamentally broken with the framework and the practices of antecedent regimes.

Thus confirming, as the Burundians say, that the peasants are supposed to be in power "through their children" with the distance of a generation via school, universities, military training and now the maquis in the name of their status as liberators of the "Burundian people". Indeed, after being put authoritatively at work since independence by the various military regimes who have succeeded in appropriating the state, it is the very children of the “people of the hills” – who for the most part have borne the brunt of the civil war – who now live by their labour.

In view of the managerial and social bankruptcy that has set in and seems insurmountable, the rupture could potentially be deeper than ethnic and regional divisions. Having brought leaders from its ranks to power, the peasantry became fully aware that beyond the atomization and disorganization of the workers of the land for which it bears responsibility, it is through the very forms of integration and participation in state power stems from its political non-existence as a class of small producers.

The essential role of the peasantry and its place in the state

It is in fact the peasantry which provides almost all the members and resources of a party-state, most of whose agrarian policy decisions are taken without consultation, including at the grassroots levels where party delegates, often peasants, exercise only executive functions. Faced with a State which, under its various public or private nominees, has imposed itself as the exclusive economic operator, it is its civil servants and, concretely, the party cadres who program and direct investments, then manage productive interventions and their fallout.

But in Burundi the acute awareness of the devaluation of the way of life of the peasants and their dispossession is based on a particular ideological configuration because, unlike many African countries where agriculture is moribund, the daily exercise of the domination suffered is weighted by the consciousness of the massive potential power, if not of the peasantry as a class, at least of the peasant order. This contained force is very real even if it is expressed indirectly in the limits imposed on the operations of productive dynamization and ideological animation.

In a country where the State cannot live without the labor offered by the producers of the earth (i.e. 30% of the GDP for 90% of the national workforce) in the form of products and export earnings, this decline on their plots maintains the feeling of "holding" the state. Widely shared, it unites the peasantry beyond its differentiations and permanently reactivates rural values which draw their strength from the secular feeling of domination of nature and integration into an order which, in the face of misery, has become for many a last line of defence.

André Guichaoua, University professor, Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne University

This article is republished from The Conversation under Creative Commons license. Read theoriginal article.

![[Editorial] 30 years later, is apartheid really over?](https://lejournaldelafrique.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/caricature-jda-apartheid-360x180.jpg)

![[Edito] Gabon and Commonwealth: the whims of Prince Ali](https://lejournaldelafrique.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/caricature-JDA-Bongo-360x180.jpg)

![[Editorial] Facebook and Twitter, more dictators than dictators?](https://lejournaldelafrique.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Caricature-JDA-FB-TW-360x180.jpg)

![[Edito] Rwanda: for the French apologies, we will have to go back](https://lejournaldelafrique.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Caricature-rwanda-JDA-360x180.jpg)

![[Edito] Guinea: Alpha Condé, the oppressed turned oppressor](https://lejournaldelafrique.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Caricature-Alpha-Conde-360x180.jpg)

![[Edito] CFA Franc: a facelift cut to measure for France](https://lejournaldelafrique.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Caricature-JDA-CFA-360x180.jpg)

![[Edito] Riyad Mahrez: One, two, three, viva l'Algérie!](https://lejournaldelafrique.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/caricature-Mahrez-360x180.jpg)

![[Edito] Niger: Mohamed Bazoum begins a delicate balancing act](https://lejournaldelafrique.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/image_6483441-1-360x180.jpg)